The Housing Question No 12: A finite resource

What the consultation on reforms to social housing allocations ignores, why new population projections take us back to square one and why housebuilders are backing Labour

Welcome to the 12th issue of my newsletter on everything to do with housing in the UK and beyond. The Housing Question is still a work in progress but if you like what you read please consider subscribing (it’s free for now) and sharing links on social media.

British homes for British people? How about building some?

A day after the government published the consultation on reforms to social housing allocations that is meant to deliver ‘British homes for British people’, its own data on social housing lettings was shining a light on the large animal with big ears and a long trunk standing in the corner.

True, the percentage of lettings going to UK nationals in 2022/23 (89.6 per cent of lead tenants) was down very slightly on 2021/22 (90.3 per cent) with 3.9 per cent going to European Economic Area (EEA) nationals and 6.5 per cent to people from other countries. But it’s hardly the surge in queue-jumping that certain newspapers may have you believe.

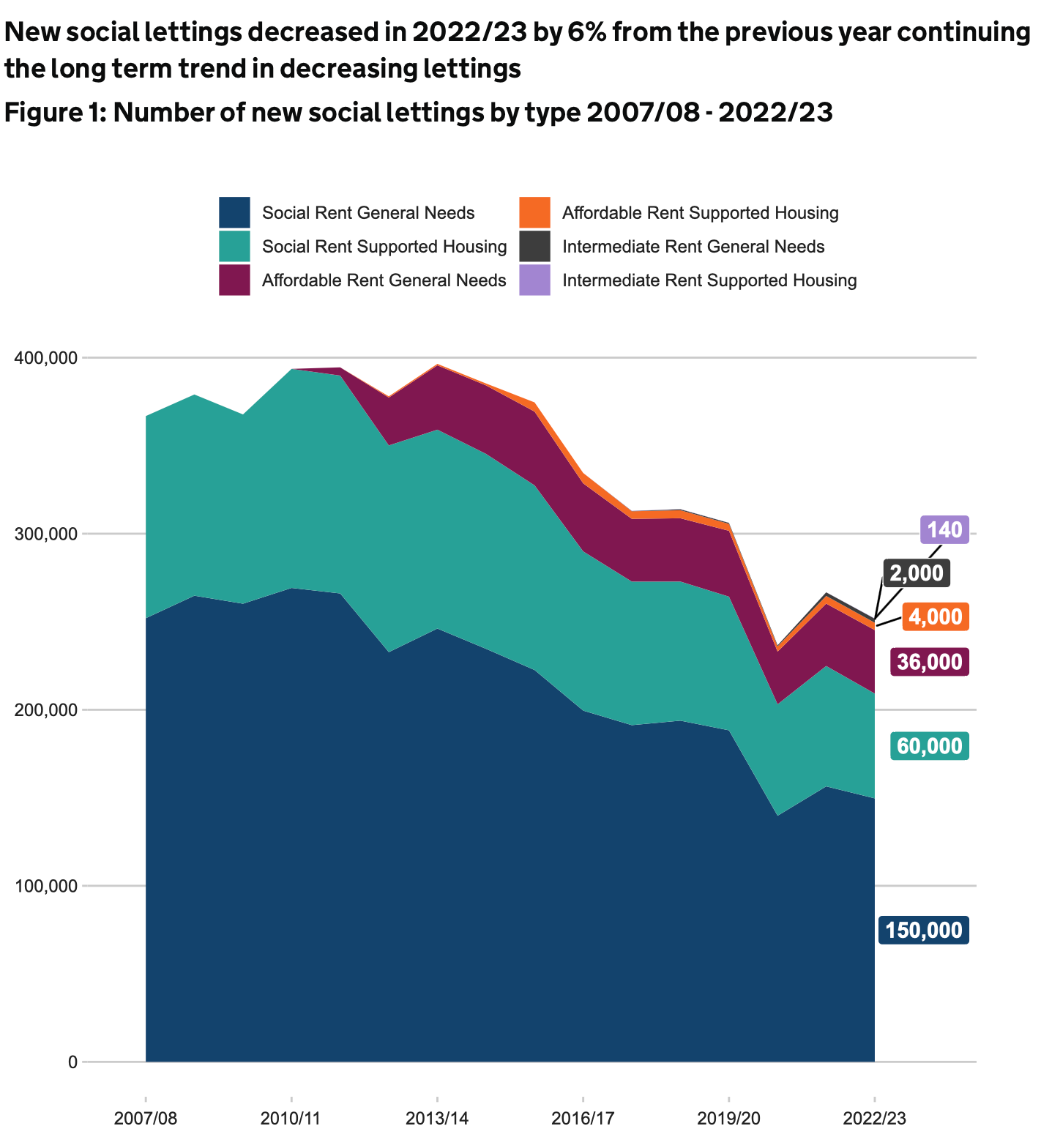

The bigger picture is how many of those ‘British [which means English] homes’ were actually available to let to anyone. The total number of social lettings fell for the ninth year in succession last year to 252,000. That was down 5.6 per cent on a year ago and 36 per cent on the recent peak of 396,000 in 2013/14. Back then 32,000 went to non-UK nationals, a slightly smaller proportion than now but still more in numerical terms than the 26,000 recorded last year.

And even that does not tell the full story: those figures represent total lettings of social, affordable, intermediate and supported housing. Lettings of social rent homes for general needs and supported housing were down 7 per cent on a year ago and 42 per cent on the 2013/14 peak. This graph from the government statistics shows the detail:

The decline reflects both the deep cuts in the Affordable Homes Programme imposed by the Conservative-led coalition and affordability pressures elsewhere in the housing system that mean fewer moves and fewer new lettings.

In his introduction to the consultation, housing minister Lee Rowley justifies the reforms to allocations on the basis that ‘social housing is a finite resource and in any compassionate society, it is incumbent upon the government of the day to ensure it is utilised in the most effective way to support those who truly need it and those who play by the rules’.

But as those new lettings figures show, social housing has become even more of a finite resource as a direct result of the actions of his government, starting obviously with the Right to Buy but extending right across the policy that should apply in that compassionate society.

Take the total stock of social homes. In an interview on the Today programme on Tuesday, the minister claimed that ‘there has been a significant increase in social housing over the last 14 years’.

That is of course only true if you blur the distinction between social and affordable housing (something that all Tory housing ministers have routinely done since 2010). As a result of cuts in funding, Right to Buy sales, demolitions and conversions to affordable rent, the number of social rent homes in England has fallen by almost 300,000 since 2010 and there is still a net loss every year.

The distinction between homes that are ‘affordable’ in relation to income (social rent) and those that are ‘affordable’ in relation to market rents (affordable rent) will become much clearer if another proposal in the consultation comes into effect.

My column for Inside Housing this week explains why it will not mean ‘British homes for British people’ or anything like it and looks in more detail at proposals including the UK connection and local connection tests.

However, the consultation also envisages a new household ‘income test’ that would apply both to get on to the waiting list in the first place and to get a social home.

Households on universal credit and housing benefit would be exempt on the basis that they have already demonstrated financial need. That accounts for 80 per cent of social lettings last year.

Some local authorities already apply varying income tests to the other 20 an income of more than £50,000 and that 80 per cent had a household income below £30,000.

It’s not clear what problem this is attempting to solve but it demonstrates a continuing obsession with high earners living in social housing.

Like the rest of the consultation, the income test would not apply to existing tenants ‘so, if tenants succeed in securing higher-paid employment after securing a social home, this will have no impact on their tenancy. This will ensure no one is penalised for improving their lot in life.’

But it is less than ten years since the the Conservative-led coalition government tried and failed to do exactly that by charging higher ‘Pay to Stay’ rents to existing council tenants with higher incomes. It could also create the same cliff-edge problem, with families finally getting a social home after years on the waiting list only to be denied it because they earn a few pounds more than the income threshold.

Whatever threshold is chosen will at least make the distinction between social rent and other forms of affordable housing much clearer. For example, shared ownership is available to households with an income of £80,000 a year (£90,000 in London).

Will that stop politicians doing the affordable/social shuffle, let alone denying responsibility for the declining supply of social housing while pinning the blame on the people applying for it? Don't count it on it.

Back to square one with population projections

Away from the political slogans, the real debate about migration and housing should be focussed on new population projections published this week by the Office for National Statistics.

The interim 2021-based projections envisage much faster growth than earlier 2020-based projections, with the UK population rising from 67 million to 73.7 million over the 15 years between mid-2021 and mid-2036. Most of the increase is due to net international migration of 6.1 people plus 541,000 more births than deaths.

This is obviously heavily influenced by recent record levels of net migration and is based on lots of assumptions that may be questionable, notably long-term net international migration settling at around 315,000 a year from mid-2028 and a mini-baby boom over the next few years.

It matters to housing because it implies (via a calculation about household sizes) a big increase in the household projections too. Far more new homes will be needed to meet demand and that in turn means the 300,000 new homes a year target set by the two main parties for England will not be enough.

The right-wing Centre for Policy Studies estimates that 382,000 a year will be needed instead. England produced just 234,000 net additional homes last year. Economist Ian Mulheirn argues that the CPS has inflated the numbers and the implied requirement is at most 238,000 new homes a year.

There are lots of moving parts here: not least how that 300,000 figure was arrived at in the first place, how we count new homes and how we account for currently unmet housing need.

And the population projections vary considerably depending on the assumptions embedded in them: the 2021-based projections essentially take us back to the 2014-based projections that were superseded by lower 2018-based projections that led many to argue that we don't need so many new homes after all.

The big difference, of course, is that far from ‘taking back control’, Brexit has led to a big increase in net migration and a political debate that focuses on empty slogans rather than solutions.

Those lower population projections were what lay behind the government’s recent surrender to Tory backbenchers with planning reforms that have diluted housebuilding targets for local areas and made them advisory. Now those projections turn out to be wrong and we are back where we started from plus more besides. As Rishi Sunak might put it, we are back to square one.

Gove’s ‘imaginary armies’

Perhaps not unrelated to that, a survey of 50 developers by Knight Frank suggests that 70 per cent support Labour to form the next government.

That is a remarkable result for anyone who remembers the 1980s - when top housebuilders were major Tory donors and Margaret Thatcher was knighting Sir Lawrie Barratt and buying one of his houses for her retirement – or even the 2010s when housebuilders were the major beneficiaries of Help to Buy.

It’s perhaps not so surprising that housebuilders are making positive noises when they expect the Labour party to form the next government and see a need to suck up to it.

But the switch also seems to reflect immense frustration over sudden lurches in policy, the constant turnover of housing ministers and above all those planning reforms, with housing secretary Michael Gove ‘bowing to nimbyism’ while claiming to be putting pressure on local authorities to bring forward local plans.

I was struck by comments in the Financial Times by Crest Nicholson chief executive that Gove’s approach was ‘like the general ordering around imaginary armies…It is not happening and it is not going to happen. Nobody fears the consequences, so they are just not doing it.’