The Housing Question No 7: An end to the freeze?

A look forward to the Autumn Statement, a look back to the reshuffle, 50 years of the building safety crisis

Welcome to the seventh issue of The Housing Question, my newsletter covering everything to do with housing. After a prolonged hiatus, I’m back on a more regular basis with some thoughts on what’s been catching my attention in the last week. The Housing Question is still a work in progress but let me know what you think and please consider subscribing (it’s free for now) and sharing on social media if you like what you read.

Cuts, caps and freezes

The signals ahead of next week’s Autumn Statement could hardly be more divisive.

On the one hand, the cut in inheritance tax set to be proposed by Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt will benefit only a tiny proportion of taxpayers, with millionaires like Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt prominent among them. A rumoured cut in stamp duty would be sold as benefitting young first-time buyers but will actually go into the pockets of existing home owners.

On the other, various wheezes are suggested to cut the cost of benefits that by definition go to the poorest. The chancellor is said to be shifting the basis for uprating benefits from the usual September rate of inflation (6.7 per cent) to the lower October rate (4.7 per cent). This would save (aka cost claimants) a permanent £3 billion, according the the Institute for Fiscal Studies. Meanwhile the Back to Work Plan launched on Thursday could create notional savings that would clear space for tax cuts even as it threatens the sick, disabled and long-term unemployed with draconian sanctions.

Perhaps the biggest issue for housing is what will happen to Local Housing Allowance (LHA) paid to private renters. LHA rates are meant to reflect the cheapest 30 per cent of rents in each local market area (though even that is a cut from the original cheapest 50 per cent). However, rates have been frozen since April 2020 while rents have risen sharply, leaving many tenants unable to find anywhere to rent within their allowance and forced to make up the shortfall from their other benefits. LHA was introduced in 2008 and was originally designed to give tenants an incentive to ‘shop around’ for a cheaper rent by allowing them to keep some of the savings. It has instead become a machine for creating rent arrears and homelessness - and controlling costs for the Treasury.

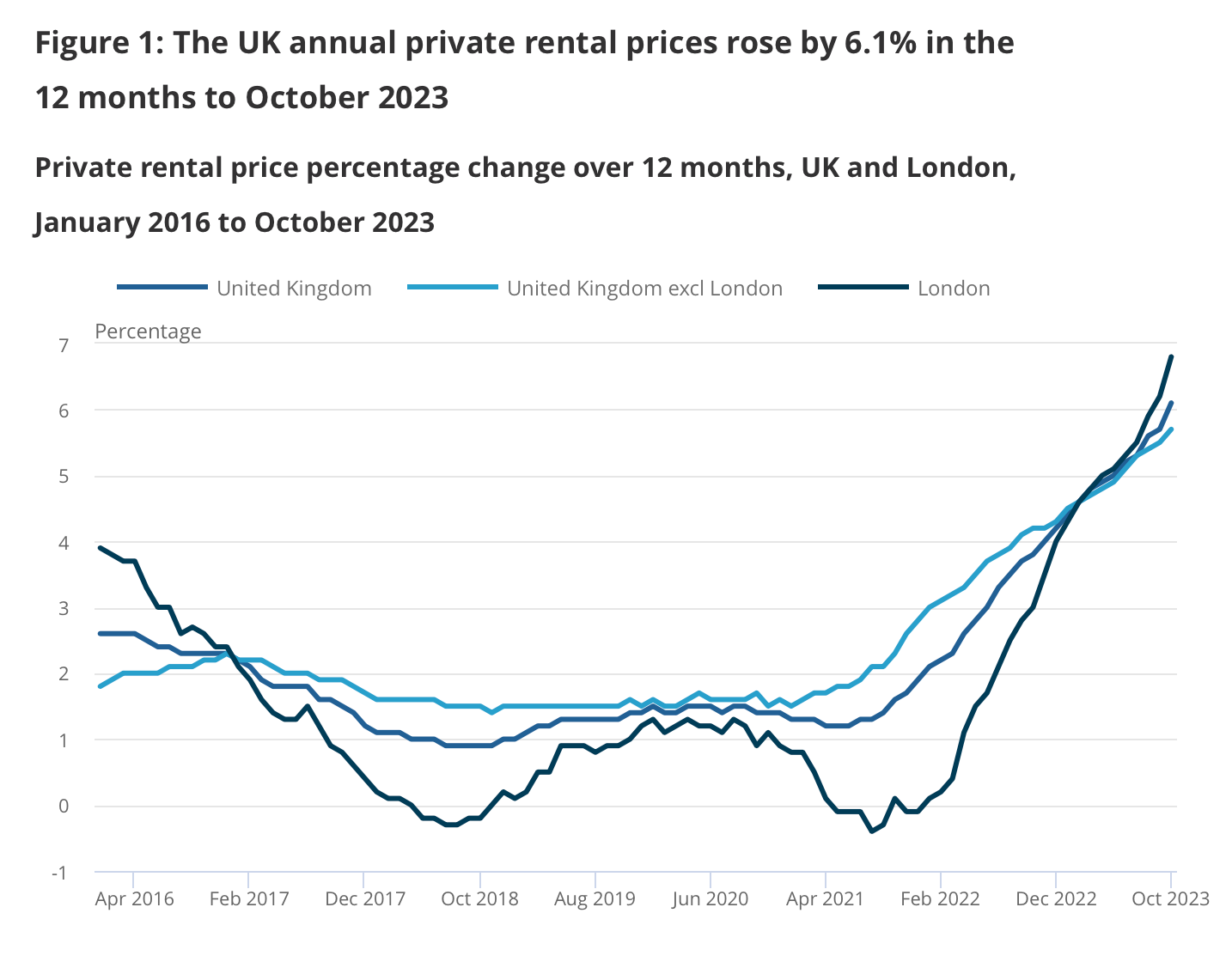

Rents for new lets show large increases: Homelet estimates a 9.6 per cent rise in the last 12 months and 31 per cent since LHA rates were last increased in April 2020. Rents for all tenancies recorded by the official Index of Private Rental Prices show smaller but still significant increases: a record 6.1 per cent in the last 12 months and 12.5 per cent since LHA rates were last increased. The vertical take-off since early 2022 is shown in the graph below.

Calls for an end to the freeze have come from local authorities, housing organisations and landlords. In Wales, for example, research by Crisis and Zoopla shows that just 2 per cent of rentals were advertised within LHA rates in the last financial year. People on the lowest incomes were having to find between £1,155 and £3,013 to bridge the gap between their LHA and their rent. In London, research for London Councils estimates that up to 22,000 households face homelessness by 2030 if the freeze goes on. Restoring LHA to the 30th percentile of local rents would actually save the public finances in the capital more than £100 million a year as a result of reduced pressure on homelessness services and other parts of the public sector, it says. Lead councillors from Labour, the Lib Dems and the Conservatives have signed a joint letter calling for an end to the freeze.

But the calls for action are not just coming from the usual suspects. Over the weekend the BBC reported that housing secretary Michael Gove and work and pensions secretary Mel Stride have written a joint letter to the prime minister and chancellor demanding an increase in LHA rates. Leaks like that ahead of Budgets and Autumn Statements are unusual so this one feels significant. However, the Treasury is said to want an increase in universal credit rates for people in work instead and resorted to its usual formulaic statement on LHA that ‘we've maintained our boost of nearly £1 billion to Local Housing Allowance while our Discretionary Housing Payments provide a safety net’.

Watch out for any hint of that misleading claim next week. The so-callled ‘boost’ came when LHA was last restored to the 30th percentile in April 2020 after years of freezes and below-inflation increases in the 2020s. The freeze ever since is the opposite of that and DHPs only make up part of the difference.

UPDATE: More optimistically, ITV News reported ‘possible movement’ on lifting the LHA freeze on Saturday.

Watch out too for what happens (or not) to the overall benefit cap that restricts the total amount of benefits that any household can receive. This was introduced in 2013 at £26,000 a year (with some exemptions and DHPs) on the basis that this represented the average earnings of a working household before being reduced to £23,000 in London and £20,000 elsewhere in 2016. Those thresholds were then frozen until they were finally increased in April (but only by the rate of inflation for one year rather than seven or nine) to £25,323 in London and £22,020 elsewhere. Like LHA, the benefit cap is a less visible way for the Treasury to control costs that applies after any decisions about uprating - a discretionary welfare state that runs alongside the benefits system.

In an optimistic scenario, Jeremy Hunt will finally unfreeze LHA rates next week. Unless these limits on overall benefits are also increased, the squeeze will just continue by other means for many renters.

When push comes to shuffle

As Marx forgot to add, housing ministers repeat themselves, the first time as a relief, the 16th time as farce.

My column for Inside Housing this week picks the bones out of a reshuffle that demonstrated only too clearly housing’s place in this government’s list of priorities.

The departure of Rachel Maclean was sadly not a surprise in itself. The pattern with which we’ve become wearily familiar runs like this: put a housing minister in place, let them develop a feel for the job and then move them on after a few months. She was the 16th housing minister under Conservative or Conservative-led governments since 2010.

This is far from the only ministerial post that prime ministers have treated like a revolving door and the pattern undermines any chance of continuity in policy. As for the Long-Term Plan for Housing (a title she claims was her idea) launched four months ago, that looks even less plausible now than it did at the time.

The timing was more of a surprise. It came a day before she was due to take the Renters (Reform) Bill into committee and weeks before (we hope) the Leasehold and Freehold Bill is due to get its first reading. True, Michael Gove is still there as housing secretary and, true, ministers follow briefs developed for them by their civil servants, but piloting two major pieces of legislation through the Commons in the year left before the election surely requires someone with a grasp of the key issues and debates to come.

Her replacement, Lee Rowley, moves sideways in the same department from his brief as junior minister for local government and building safety to become the seventh housing minister in the last two years. That counts him twice since he can also boast all of 49 days experience as housing minister under the Liz Truss regime last year. It does at least mean that he will not be starting totally from scratch but his appointment only came after persistent rumours that others had turned down the post.

The sacking itself was more of a mystery. Departing ministers are often given the chance to resign first but Rachel Maclean tweeted out the news along with a pointed reminder about the timing:

Even a cursory glimpse at her Twitter feed will tell you that she was relishing the job and unhappy to leave. Gove and Cabinet colleague Kemi Badenoch are rumoured to have made unsuccessful appeals to save her job, leading me to speculate that the sacking was partly a move to put Gove in his place.

However, ITN’s Robert Peston has another explanation: her sacking was actually triggered by a tweet last month.

As Peston says, leaking what’s in the King’s Speech before it happens is never a problem when Downing Street does it. It was also not a problem when briefed by ‘Whitehall sources’ to The Sunday Times earlier that same day. Or was it?

I would say we can’t go on like this – except that we do in every reshuffle. It could be just the chance for Esther McVey, housing minister number nine since 2010, to demonstrate her worth as minister for common sense. I have a funny feeling they don’t mean that kind of common sense.

Structural problems, systemic issues

The evacuation of 400 residents from a tower block in Bristol this week is a stark illustration of the continuing after-shocks of the crisis that followed a fatal incident at a tower block in London.

Except that I am not talking directly about the Grenfell Tower fire that killed 72 people in 2017 but the partial collapse of Ronan Point almost 50 years earlier that killed four people and injured 17 more. That raised the alarm about the structural integrity of panel system blocks built in the 1950s and 1960s and was meant to lead to an extensive programme to strengthen them.

One of the most shocking revelations that emerged in the wake of widespread concern about building safety after Grenfell was that the strengthening had never happened in some cases. Significant concerns remain about the safety of large panel system blocks.

Pete Apps (see below) has a story in Inside Housing this week about a panel of experts convened by the government that warned it about major risks and a market ‘prioritising profit over safety’. The panel urged ministers to write to landlords with large panel blocks but the letter was not sent.

Barton House in Bristol was built in 1958, which would make it one of the first wave of tower blocks built after the government changed the subsidy regime to incentivise them and major contractors began to license systems from Scandinavia like the one used at Ronan Point. At the Ronan Point inquiry evidence emerged of corners being cut on site, with missing reinforcement and newspapers stuffed into cavities between poorly installed panels. Surveys conducted for the council by structural engineers on three of the flats in Bristol showed that it had not been built to the original specifications and would be unsafe in the event of a fire, explosion or high impact.

Around 300 adults and 100 children were asked to leave the block on Tuesday afternoon. Most are now in temporary accommodation or staying with friends and family.

On my reading list

Here are some other housing-related Substacks that are well worth checking out.

Posts by Michael Byrne of University College Dublin that cover everything to do with housing in Ireland and beyond. Interesting both for the latest academic debates and for housing policy debates in Ireland that illuminate the ones happening elsewhere (see especially reform of the private rented sector).

Posts by Pete Apps, housing journalist and author of Show Me the Bodies, his book published in 2022 on the build-up to the Grenfell Tower fire. Fairly new to Substack but already looks like essential reading on the building safety crisis and housing more generally.

Posts by economist Cameron Murray that seems to have morphed from a Substack into a think tank. Mainly focussed on Australia but keyed into debates on housing and economics more generally – and especially those on housebuilding, supply and land.